The Anxiety Toolkit

By Lara Trevino, AGNP-C, MSN and Molly Sherb, PhD

Your brain is constantly responding to your environment by connecting and rewiring the connection between brain cells (synapses) so you can function in daily life. For example, you meet a new colleague at work and you remember their name the next day. Neuroplasticity is your brain’s ability to form and reorganize synaptic connections in response to your experiences. While we all know that our brains are essential to perform daily life activities, we are not always cognizant of how our lifestyle choices impact our brain’s regulation of stress and anxiety. Let’s discuss some concrete lifestyle tools to manage anxiety.

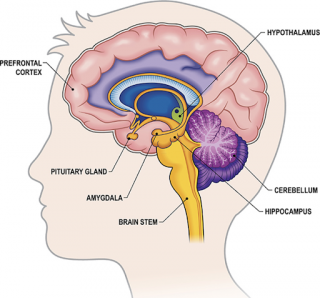

Let’s meet your brain

Prefrontal Cortex: The CEO of your brain. It helps you differentiate conflicting thoughts, determine future consequences of activities, and regulate emotions. This is the part of your brain that pumps the brakes when you feel frustrated and want to do something you may regret.

Amygdala: Your emotional gas pedal. This is the part of your brain that activates your fight or flight response. World renown rock climber Alex Hannold scales faces of mountains without ropes where the consequence of a mistake can be death. When examined on MRI, he has an underfunctioning amygdala.

Hippocampus: A highly plastic brain region that houses anxiety cells that can dial up and dial down anxiety.3,4

Lifestyle modifications to treat anxiety

Exercise

For anxiety, the more exercise the better.5 For example, more than six weeks of running has been shown to change the structure of cells in your hippocampus and increase anti-anxiety neurochemicals.1,3 Studies have shown that runners often have hippocampi that respond differently to stress in the long term. Your brain chemistry changes by increasing the bioavailability of multiple anti-anxiety neurochemicals. The American College of Cardiology recommends 30-45 minutes of cardio three to four times per week. Strength training exercises for all major muscle groups are recommended at least twice per week.

Nutrition

The relationship between your brain and your gut is a two-way street way beyond just digestion and absorption of nutrients. Uma Naidoo, MD is a Nutritional Psychiatrist at Harvard Medical School that specializes in dietary changes to treat symptoms of anxiety. Dr. Naidoo hypothesizes that high fat and high carbohydrate diets change your brain chemistry by decreasing serotonin levels in some brain regions. The decrease in serotonin levels, in combination with additional genetic and environmental factors, contribute to increased anxiety.1,2 To keep anxiety symptoms at bay, Dr. Naidoo advises a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids like fatty fish, probiotic rich foods including kefir, sauerkraut and plenty of vegetables.

Caffeine

Studies show that caffeine intake over 400 mg (a Starbucks venti) per day can stimulate a brain region that processes threats and slows down parts of your brain that regulate anxiety.1,2 The result of caffeine intake over 400 mg is worsening anxiety. If you like to drink coffee throughout the day, then consider smaller servings like 80-100 mg Nespresso cups before 11am and a decaf coffee in the afternoon.

Mindfulness

Create a wake up and wind down routine

Wake Up

Make the commitment to wake up mindfully in order to ground yourself before the start of the day. Engage in one morning activity (e.g., brush your teeth/take a shower/make breakfast/meditate) before turning on the news, checking email, or looking at your phone.

Wind Down

Create space between when you end work and when you get into bed. Choose a relaxing activity (call a friend, watch a funny show, meal prep, drink decaf tea) each night to create a transitional space between work and bedtime—this can help cue your body for sleep. For a deeper dive on sleep, see our article on Sleep.

Use all of your senses (taste, sight, sound, smell, touch) to bring yourself into the present moment. You can do this with any of your routine daily activities like drinking your cup of coffee, taking a shower, brushing your teeth. Use all your senses to bring your attention to the present moment—what does the water from the sink sound like as it rushes out of the faucet, what does the minty toothpaste taste like? What does the brush feel like on your teeth? When you are focused on physical details you are less likely to be focused on your internal thoughts.

Focus on bringing down the temperature literally and figuratively during moments of high stress or anxiety. Use ice packs or splash cold water on your face to help send the “cool down” message to your body.

Engage in deep breathing to combat shallow breathing that occurs during highly anxious moments. Breathing in a 4-2-6 pattern can be helpful—breathe in for 4 seconds, hold for 2, and exhale for 6 seconds. This pattern ensures that you are fully emptying out your lungs before taking the next breath by making your exhale longer than your inhale.

How The Health Center can help

At The Health Center, we specialize in treating every patient as an individual and addressing your unique mental health needs.

Our Personal Health Navigators are available to help answer questions. Call 646.819.5100, or email membership@healthcenterhudsonyards.com for assistance in scheduling an appointment.

Not a member yet?

Learn about membership for yourself or your household and get your flu shot, COVID-19 tests and vaccines, and ongoing virtual or in-person care from top NYC providers.

References:

- American Heart Association recommendations for physical activity in adults and kids. www.heart.org. (2022, July 28). Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/fitness/fitness-basics/aha-recs-for-physical-activity-in-adults

- de Sousa Fernandes, M. S., Ordônio, T. F., Santos, G. C. J., Santos, L. E. R., Calazans, C. T., Gomes, D. A., & Santos, T. M. (2020, December 14). Effects of physical exercise on neuroplasticity and Brain Function: A systematic review in human and Animal Studies. Neural plasticity. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7752270/#B25

- Ghasemi, M., Navidhamidi, M., Rezaei, F., Azizikia, A., & Mehranfard, N. (2021, December 6). Anxiety and hippocampal neuronal activity: Relationship and potential mechanisms – cognitive, affective, & behavioral neuroscience. SpringerLink. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13415-021-00973-y

- Hamilton, J. (2018, January 31). Researchers discover ‘anxiety cells’ in the brain. NPR. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/01/31/582112597/researchers-discover-anxiety-cells-in-the-brain

- John J. Ratey, M. D. (2019, October 24). Can exercise help treat anxiety? Harvard Health. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/can-exercise-help-treat-anxiety-2019102418096

- Kim, S., Meckler, M., & Faris, D. (2022, March 20). Does alcohol cause anxiety? experts explain why you hate Sundays. Newsweek. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.newsweek.com/alcohol-cause-anxiety-mental-health-experts-1687667

- Lach, G., Schellekens, H., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2018). Anxiety, Depression, and the Microbiome: A Role for Gut Peptides. Neurotherapeutics : The Journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics, 15(1), 36–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-017-0585-0

- Linehan, M., M., (2014). DBT Training Manual. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Luczynski, P., Whelan, S. O., O’Sullivan, C., Clarke, G., Shanahan, F., Dinan, T. G., & Cryan, J. F. (2016). Adult microbiota-deficient mice have distinct dendritic morphological changes: differential effects in the amygdala and hippocampus. The European journal of neuroscience, 44(9), 2654–2666. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.13291